Battle of An Ninh

18 September 1965

The Military Advisory Command Vietnam (MACV) Summary for 1965 contains the following entry:

The 52nd Aviation Battalion's 1965 History contains an equally brusque entry:

Neither entry says anything useful about what happened or even where it happened - but the 18 Sep 1965 engagement at An Ninh was the 101st Airborne Division's, if not America's, introduction to the North Vietnamese Army.

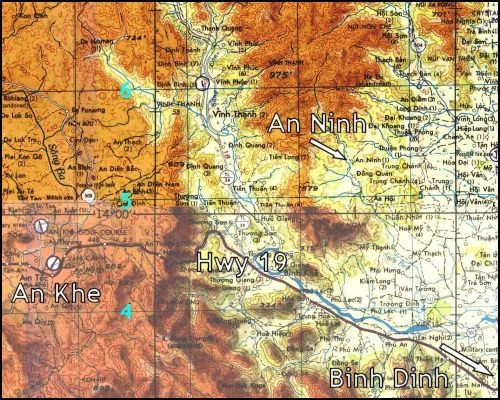

An Ninh was and remains a tiny village in a remote river valley some kilometers north of National Route 19, which joins the Central Highlands to the coast. The village itself had little strategic value, but its location did ... it provided a refuge within easy striking distance of Highway 19. The mountains north of An Ninh had been a rebel stronghold since the days of the French Indochina war, and the only difference in 1965 was who was holed up in the hills.

The 1st Brigade, 101st Airborne Division (three maneuver battalions, 2nd Bn, 502nd Infantry, 1st and 2nd Bns, 327th Infantry) arrived at Cam Ranh Bay on 28 July; at the end of August it was moved to An Khe in the Central Highlands and assigned two tasks - securing a base area for the soon-to-arrive 1st Cavalry Division and keeping Highway 19 open between the port city of Qui Nhon and the Central Highlands cities of Pleiku and An Khe. During its first six weeks at An Khe the 1st Bde gained little experience with the North Vietnamese Army, a situation that would be rectified at An Ninh. The 1st Bde had few helicopters, but the 52nd Aviation Battalion at Pleiku City had UH-1s and the Marines at Qui Nhon had UH-34s - not many of either type, but enough to provide the 1st Bde with limited air mobility. Once the 1st Cav arrived and set up shop in and to the west of An Khe, 1st Bde, 101st Abn turned its attention to the Highway 19 problem.

By mid-September recon patrols and air surveillance had established that a VC/NVA unit was using An Ninh as a training ground, with emphasis on anti-helicopter operations. Radio intercepts suggested that the 95th NVA Battalion was based around An Ninh, a situation that caused 1st Bde to plan an air assault on the village. The original plan was to place elements of the 327th Infantry north of and the 2/502 south of An Ninh, with the intent of having 2/502 sweep north, pushing the VC/NVA into the 327th's blocking forces. Operation GIBRALTAR was underway.

As noted in the 52nd Avn Bn History, GIBRALTAR was executed on 18 September. While 2/327th Infantry was lifted into place as expected in two locations 2 kilometers NE and NW of the village, the Commanding Officer of 2/502 made an in-flight decision to land just at the southern edge of An Ninh, thereby eliminating the 2 kilometer approach march for 2/502 and hopefully increasing the assault's shock value. As it turned out, the decision was a bad one - the helos carrying 2nd Bn, 502nd Infantry landed in the midst of the 95th NVA Bn's training ground. Even worse, the selected site was a set of small rice paddies surrounded on three side by hills, and the VC/NVA held the high ground.

The Americans did have surprise on their side and the first wave of troops were landed without significant opposition - but there weren't enough helicopters to move two battalions of troops (well over 1000 men, including attachments) into place quickly. By the time the second wave of 2/502 troopers arrived the NVA had recovered from their initial surprise and took the helos under heavy fire. While they could not halt the landings, the VC/NVA could and did disrupt them, with the result that elements of the 2/502 were landed erratically rather than in a smooth stream of paratroops inserted according to plan.

The US position quickly deteriorated further. The supporting artillery battalion was moving by road, the road wasn't very good, and the 2/502 paratroops were 2 kilometers further north than expected. The result was that the initial landing, and much of the day's fighting, was accomplished without artillery support. Anticipated fixed-wing air support did not arrive until mid-afternoon1 so that only the few helicopter gunships were available for initial support. 2/502, inserted incompletely and in piece-meal fashion, was on its own.

The main body of 2/502 - about 200 men - was in place on the southern edge of An Ninh. A much smaller group from Alpha 2/502, roughly a platoon, had been landed on a small hill about a kilometer distant before the helo insertions were halted by enemy fire. When the 2/327's blocking force northwest of An Ninh was directed to move toward the 2/502 position they found they had been landed 4 kilometers rather than 2 kilometers from the village and had to make a forced march toward An Ninh. While en route this group was reinforced with additional elements of 2/327 as well as soldiers from the 1st Cav Div's 9th and 17th Cavalry Regiments - but they could not close on An Ninh before nightfall and were forced to set up a defensive perimeter about a mile distant.

The VC/NVA emplaced on the surrounding hills had clear fields of fire into the LZ area and had heavy machine guns to exploit their advantage. It was obvious to the 2/502 men that these positions had to be cleared before there could be any realistic hope of securing the LZ - and they were taken by means of an up-hill bayonet charge. The resulting reduction in fire into the LZ permitted the resumption of helo operations, now predominantly 1st Cavalry Division helos operating from An Khe. By midafternoon the 1st Cav Div's airlift platoons were bringing in the remainder of 2/502's paratroops, while their heavy-lift helos moved two artillery batteries into position. Bien Hoa-based fixed wing aircraft also had arrived, providing heavier air support than could the helicopter gunships. The increasing weight of US supporting fires and the increasing number of paratroopers on the ground gradually turned the tide, and by nightfall 2/502 had cleared the village proper and established a defensive perimeter. Even so, there were more VC/NVA than US soldiers in the area and sporadic, close-in fighting continued through the night ... but after dawn on the 19th the 2/327 soldiers moved into the village area without making contact with the VC/NVA; they had disappeared.

About 250 enemy dead were left on the battlefield; by comparison 16 Americans are known to have died in the fighting, and another died 11 years afterwards. This comparison fails to reflect the reality, though, because a great many of the US soldiers who actually fought the battle were wounded - the 2nd Battalion, 502nd Infantry was victorious but at considerable cost.

The 17 US soldiers known to have died as a result of the battle at An Ninh were

- A Co, 228th Aslt Spt Helo Bn

- SSG Larry L. Truesdale, Lima, OH

Note: CH-47A tail number 63-07908

- A Co, 502nd Avn Bn

- 1LT Patrick A. Deck, Chevy Chase, MD

Note: In a coma for 11+ years; died of wounds 02 Feb 1977

- C Co, 1st Bn, 14th Infantry

- PFC Paul E. Rytter, Bakersfield, CA

Note: TDY door gunner with 117th Avn Co, 52nd Avn Bn; helo unknown

- C Btry, 2nd Bn, 320th Artillery

- 2LT Edward H. Fox, Plainview, TX

Note: Forward Observer with 2/502 Infantry

- 2nd Bn, 502nd Infantry

- MAJ Herbert J. Dexter, Decatur, IL, HQ Company(Dist Svc Cross)

- CPT Robert E. Rawls, Royal Oak, MI, C Company

- SSG Johnnie W. Faircloth, Cordele, GA, B Company(Silver Star)

- SSG Roynald E. Taylor, Metter, GA, B Company

- SSG George E. Burchett, Bloomington, IL, HQ Company

- SP4 Joe L. Meek, Exeter, CA, B Company

- SP4 Ernest L. Miller, Detroit, MI, B Company

- SP4 Frank Boynton, Columbus, GA, C Company

- PFC Ernest K. Gerhardt, Modesto, CA, C Company

- PFC Leroy Hicks, Newport, NJ, C Company

- PFC Jerry D. Underwood, Louisville, KY, C Company

- PFC Johnnie P. Winfrey, Bay City, TX, C Company

- D Co, 1st Bn, 5th Cavalry

- SSG Duane C. Schell, Spokane, WA

Note: Medic aboard 1st Cav medevac helo, tail number unknown

In 2003 Mr. Mallon Faircloth, whose brother Staff Sergeant Johnnie Faircloth received a posthumous Silver Star for his actions at An Ninh, wrote Behind the Names, a description of the fight. The synopsis given above draws heavily on Mr. Faircloth's work - but he in no way is responsible for errors of omission or commission in the summary. Mr. Faircloth and The Virtual Wall independently identified the US servicemen who died as a result of the An Ninh fight and agree entirely on 16 men - with one exception those listed above. The exception is a helicopter pilot, 1LT Patrick A. Deck, who received a severe head wound during the assault. 1LT Deck survived in a coma for eleven years before he died on 02 Feb 1977. His name was added to the Wall on Veterans' Day 1983.

Behind the Names includes four Air Force personnel:

- Capt David E. Benson, Doraville, GA, 6250th Support Sqdn

- Capt Fred R. Tice, Lexington, PA, 35th Troop Carrier Sqdn

- Capt Thomas J. Tolliver, Union, MO, 6250th Support Sqdn

- SSgt Walter O. Tramel, Owatonna, MN, 35th Troop Carrier Sqdn

Captains Benson and Tice are included as "Air Force pilots from Bien Hoa Air Base ... killed when their planes were shot down" at An Ninh (Faircloth, pp48,54,64). Captain Tolliver and SSgt Tramel are named as the crew of an L-19 (O-1E) Forward Air Control aircraft which crashed immediately after take-off from Qui Nhon (Faircloth, pp32,48,64-65).

Hobson's Vietnam Air Losses lists Captain Tice and SSgt Tramel as crewmen and Captains Benson and Tolliver as passengers aboard C-130A tail number 55-0038 which crashed in Qui Nhon harbor during approach to Qui Nhon airfield on 18 Sep 1965 (Hobson, p32). The US Air Force's casualty list and the DoD casualty file both support Hobson's findings. Tolliver and Benson were indeed Forward Air Control pilots, but they were not functioning in that role when they died.

A FAC aircraft did go down at Qui Nhon on 18 Sep: O-1E tail number 56-4167 was destroyed in a forced landing immediately after take-off. The pilot, 1stLt G. E. Walters, and his unknown observer survived the incident. There is no record of any fixed-wing aircraft losses at An Ninh.

Mr. Faircloth also mentions two men who survived An Ninh but died afterwards:

- SP4 Earnest A. Tucker, C Co 2/502 Infantry. SP4 Tucker was one of 21 men killed when CH-47A tail number 64-13138 went down near Nhon Co, Quang Duc Province, on 04 May 1968.

- SP4 Joseph R. Sweda, C Co 2/502 Infantry. Died of malaria on 25 Oct 1965, five weeks after An Ninh.

The fight at An Ninh can and should be viewed as an outstanding example of American courage and tenacity under fire; the men directly involved in the fight cannot be faulted. There is room to question at least two of the decisions taken before battle was joined:

- On 18 September the 1st Cavalry Division, with over 400 helicopters, was firmly in place in Binh Dinh Province, primarily at An Khe. It is incomprehensible why 1st Cav Div assets were not used to provide airlift for the 1st Bde, 101st Abn paratroopers - but apparently they weren't invited to the party. The first lifts into An Ninh were essentially unopposed. Had enough aircraft been used to lift the entire 2/502nd Infantry in a continuous stream most or all of the battalion would have been on the ground when the fighting started. In fact, the aircraft were available but were not used; instead, total reliance was placed on the two dozen aircraft available from the 52nd Aviation Battalion and the Marine squadron at Qui Nhon.

- LTC W. K. G. Smith, Commanding Officer 2nd Bn, 502nd Infantry, made the in-flight decision to land on the southern edge of An Ninh rather than 2 kilometers to the south as planned, and did so knowing his battalion could only be brought in piece-meal. He also knew that the LZ would be out of artillery range and hence wholly reliant on air support. When VC/NVA resistance made further airlift impossible and fixed-wing air support failed to materialize LTC Smith found himself without a "Plan B".

There were lessons to be learned from An Ninh as well:

- The VC and NVA were very competent soldiers, particularly when fighting on their own ground. This lesson was relearned in the Ia Drang Valley a month afterwards.

- VC/NVA tactical doctrine, developed over 25 years of fighting the Japanese, French, and South Vietnamese, placed emphasis on always maintaining a secure route for withdrawal. At An Ninh, VC/NVA fighting forces were active until shortly before dawn on 19 Sep - but when the 327th Infantry arrived shortly after dawn they did so without opposition. The VC/NVA had disappeared, a tactic that would confound US forces throughout the war.

- The VC/NVA tactical doctrine also emphasized camoflage and concealment, and they were masters of the art. By September 1965 the Marines had already learned this lesson in Quang Nam Province and the 173rd Abn Bde in War Zone D; the 1st Bde, 101st Abn learned it at An Ninh.

- Maximum use had to be made of US supporting fires, and those fires had to be available when needed. There were other occasions when US forces moved out in front of their artillery support, and in most such instances the decision to do so resulted in painful consequences.

- The Army's air-mobile concept worked, but at An Ninh it didn't satisfy Nathan Bedford Forrest's dictum: "git thar fust with the most men." The Civil War cavalry general probably would have dropped dead if he saw a herd of unused horses off to the side while his men took turns riding just a few.

- VC/NVA forces allowed to disappear today would reappear tomorrow, and the day afterwards as well. The Suoi Cai Valley lies just west of An Ninh; during the first weeks of October 1965 the 1st Cavalry Division was fighting the VC/NVA there - the same VC/NVA units which had withdrawn from the fight at An Ninh.

1

According to Faircloth, US Air Force aircraft at Qui Nhon were grounded due to contaminated fuel and there was an understandable delay while USAF assets at Bien Hoa Air Base were retasked for and flew to An Ninh.

|